Revolutionary mystic and literary icon with his feet on the ground

Ernesto Cardenal Nicaraguan poet and priest 1925-2020

When a government-backed mob burst into Managua’s cathedral this week yelling “traitor”, the target of their anger, Ernesto Cardenal, was lying dead in a flag-draped coffin at the front.

The Nicaraguan poet-priest, a mystic and Marxist revolutionary who has died aged 95, battled the Somoza regime that ruled the country for four decades and was also once an ally of President Daniel Ortega, who took power after the Sandinista revolution triumphed in 1979.

But Cardenal became a fierce critic of the regime after increasing disgust with what he said had become another dictatorship; Mr Ortega has ruled Nicaragua for 24 of the past 41 years.

“They pursued him to his death and even then, wouldn’t let him rest,” said Sergio Ramírez, a fellow writer and disenchanted former Sandinista vice-president, who nurtured a close friendship with the poet during the 40 years that they lived as neighbours.

Ironically for a cleric who once challenged the Catholic church’s authority, it was the Vatican that came to Cardenal’s defence when supporters of Mr Ortega and his powerful wife, Rosario Murillo, barged into the cathedral.

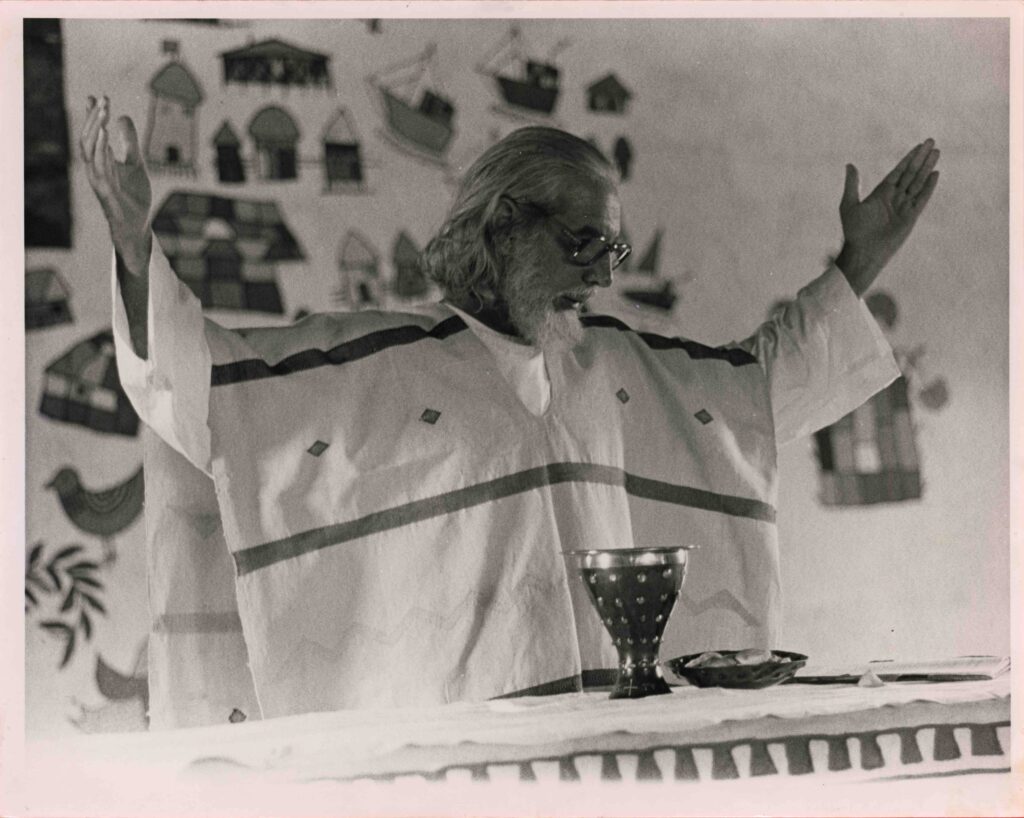

Wearing the Sandinistas’ red and black scarves and chanting government slogans, they disrupted the funeral mass under way for the priest who, with his shock of white hair and trademark white peasant shirt and black beret, was a Latin American literary icon.

Appealing for calm, papal nuncio Waldemar Stanislaw told the mob he would get down on his knees if necessary. He then continued the service for a man who had been a leading light in the liberation theology movement that preached social justice for the poor and freedom for the oppressed.

It was a sign of how respected Cardenal, who once said “Christ led me to Marx”, had become.

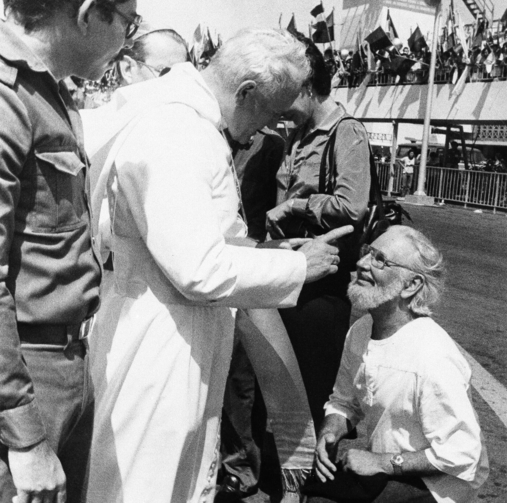

In 1983, after resisting the church’s demand that he quit his post as culture minister in the new Sandinista government, Cardenal’s attempt to greet Pope John Paul II on his arrival in Managua earned a stern rebuke.

As Cardenal knelt to kiss the Pope’s ring, John Paul wagged his finger in Cardenal’s face and told him sternly to “straighten out your position with the church”. When he did not, Cardenal was stripped of his right to conduct priestly duties, a ban that lasted over 30 years.

Born into a wealthy family in Granada on the shores of Lake Nicaragua on January 20 1925, Father Cardenal once told an interviewer he was “obsessed with sex” in his youth. He studied literature in Mexico and at Columbia University in New York, where he read Ezra Pound and Walt Whitman.

Back in Nicaragua, he took part in a 1954 plot to topple Anastasio “Tacho” Somoza and briefly went into hiding before a spiritual calling led him to a Trappist monastery in Kentucky. There he met Thomas Merton, a friendship that spawned a famous correspondence between the two poet-priests.

Cardenal retained monastic ways throughout his life, waking at 3am every day to meditate, Mr Ramírez said.

But the contemplative life was not for him. After his ordination in 1965, he founded a pastoral artistic community on the Solentiname Islands on Lake Nicaragua — where he wanted his ashes returned. The community went on to become a revolutionary base of sorts in the armed struggle against the Somoza dynasty.

Cardenal counted a trip to Cuba in 1970 as a turning point. “My first conversion was religious; in Cuba, I converted to revolution,” he told Nicaragua’s ConfidencialTV. When the Sandinistas triumphed, he became culture minister but quit in 1987 and became a vocal critic — resulting, he said, in political persecution.

Conversational in tone, his work ranged from historical and political works to a poetic exploration of his fascination with science and the cosmos, through which he discerned the hand of God the creator. Scientific American, along with the New Yorker, were among his magazine subscriptions. Nominated for the Nobel literature prize several times, he once said the accolade only appealed because it came with “a lot of money which I’d give to the poor”.

Despite recent poor health, which Mr Ramírez said forced him to curb his taste for rum and fried food, Cardenal’s literary output remained prolific. In 2019, Pope Francis also lifted the canonical sanctions against the ailing Cardenal, effectively reinstating him as an active priest.

Writing in El País newspaper, Gioconda Belli, a Nicaraguan writer and friend, called him a “poet of the universe . . . a mystic, but with his feet firmly on the ground”.

Jude Webber

A 1970 trip to Cuba was a turning point. ‘My first conversion was religious; in Cuba, I converted to revolution’The Nicaraguan poet-priest, a mystic and Marxist revolutionary who has died aged 95, battled the Somoza regime that ruled the country for four decades and was also once an ally of President Daniel Ortega, who took power after the Sandinista revolution triumphed in 1979.

But Cardenal became a fierce critic of the regime after increasing disgust with what he said had become another dictatorship; Mr Ortega has ruled Nicaragua for 24 of the past 41 years.

“They pursued him to his death and even then, wouldn’t let him rest,” said Sergio Ramírez, a fellow writer and disenchanted former Sandinista vice-president, who nurtured a close friendship with the poet during the 40 years that they lived as neighbours.

Ironically for a cleric who once challenged the Catholic church’s authority, it was the Vatican that came to Cardenal’s defence when supporters of Mr Ortega and his powerful wife, Rosario Murillo, barged into the cathedral.

Wearing the Sandinistas’ red and black scarves and chanting government slogans, they disrupted the funeral mass under way for the priest who, with his shock of white hair and trademark white peasant shirt and black beret, was a Latin American literary icon.

Appealing for calm, papal nuncio Waldemar Stanislaw told the mob he would get down on his knees if necessary. He then continued the service for a man who had been a leading light in the liberation theology movement that preached social justice for the poor and freedom for the oppressed.

It was a sign of how respected Cardenal, who once said “Christ led me to Marx”, had become.

In 1983, after resisting the church’s demand that he quit his post as culture minister in the new Sandinista government, Cardenal’s attempt to greet Pope John Paul II on his arrival in Managua earned a stern rebuke.

As Cardenal knelt to kiss the Pope’s ring, John Paul wagged his finger in Cardenal’s face and told him sternly to “straighten out your position with the church”. When he did not, Cardenal was stripped of his right to conduct priestly duties, a ban that lasted over 30 years.

Born into a wealthy family in Granada on the shores of Lake Nicaragua on January 20 1925, Father Cardenal once told an interviewer he was “obsessed with sex” in his youth. He studied literature in Mexico and at Columbia University in New York, where he read Ezra Pound and Walt Whitman.

Back in Nicaragua, he took part in a 1954 plot to topple Anastasio “Tacho” Somoza and briefly went into hiding before a spiritual calling led him to a Trappist monastery in Kentucky. There he met Thomas Merton, a friendship that spawned a famous correspondence between the two poet-priests.

Cardenal retained monastic ways throughout his life, waking at 3am every day to meditate, Mr Ramírez said.

But the contemplative life was not for him. After his ordination in 1965, he founded a pastoral artistic community on the Solentiname Islands on Lake Nicaragua — where he wanted his ashes returned. The community went on to become a revolutionary base of sorts in the armed struggle against the Somoza dynasty.

Cardenal counted a trip to Cuba in 1970 as a turning point. “My first conversion was religious; in Cuba, I converted to revolution,” he told Nicaragua’s ConfidencialTV. When the Sandinistas triumphed, he became culture minister but quit in 1987 and became a vocal critic — resulting, he said, in political persecution.

Conversational in tone, his work ranged from historical and political works to a poetic exploration of his fascination with science and the cosmos, through which he discerned the hand of God the creator. Scientific American, along with the New Yorker, were among his magazine subscriptions. Nominated for the Nobel literature prize several times, he once said the accolade only appealed because it came with “a lot of money which I’d give to the poor”.

Despite recent poor health, which Mr Ramírez said forced him to curb his taste for rum and fried food, Cardenal’s literary output remained prolific. In 2019, Pope Francis also lifted the canonical sanctions against the ailing Cardenal, effectively reinstating him as an active priest.

Writing in El País newspaper, Gioconda Belli, a Nicaraguan writer and friend, called him a “poet of the universe . . . a mystic, but with his feet firmly on the ground”.

Jude Webber

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49854/zero-hour

No comments:

Post a Comment